An interview with Jock Zonfrillo: how he has codified indigenous culinary traditions with a modern twist, recovering products with an ancient history.

I arrived at Ca' Granda as a member of the board.

I was an architect in the health sector, and it frightened me: what added value could I ever bring?

When exploring the historical administrative archives of Ca' Granda and looking at the documents, I discovered that this is a rather special hospital: it encompasses an incredible world of cultural heritage, art, beauty, agriculture and the environment.

It has a unique history, which exists in no other hospital in the world.

Ospedale Maggiore, today the Policlinico, Milan General Hospital, is one of the oldest hospitals in Italy, founded by Duke Francesco Sforza in 1456. The building is located between Via Francesco Sforza, Via Laghetto and Via Festa del Perdono, close to the Basilica of San Nazaro in Brolo. The work of the Florentine architect Filarete, and one of the first renaissance buildings in Milan.

The hospital acquired the name "Ca' Granda de' Milanesi", both for the quality of its hospitality for patients of every social class and origin, including strangers and foreigners, and for its ability to attract volunteer workers and the donations of benefactors.

From the very beginning, people were racing to donate to the Hospital: there were those who gave eggs and chickens to provide food for the patients, and those, like the Pope, who donated land, not only to give the hospital an income from their rent, but also to cultivate medicinal herbs, the base of many treatments in those centuries, and to raise animals.

All this managed to satisfy the needs of the hospital, which not only treated patients, but also gave refuge to the poor.

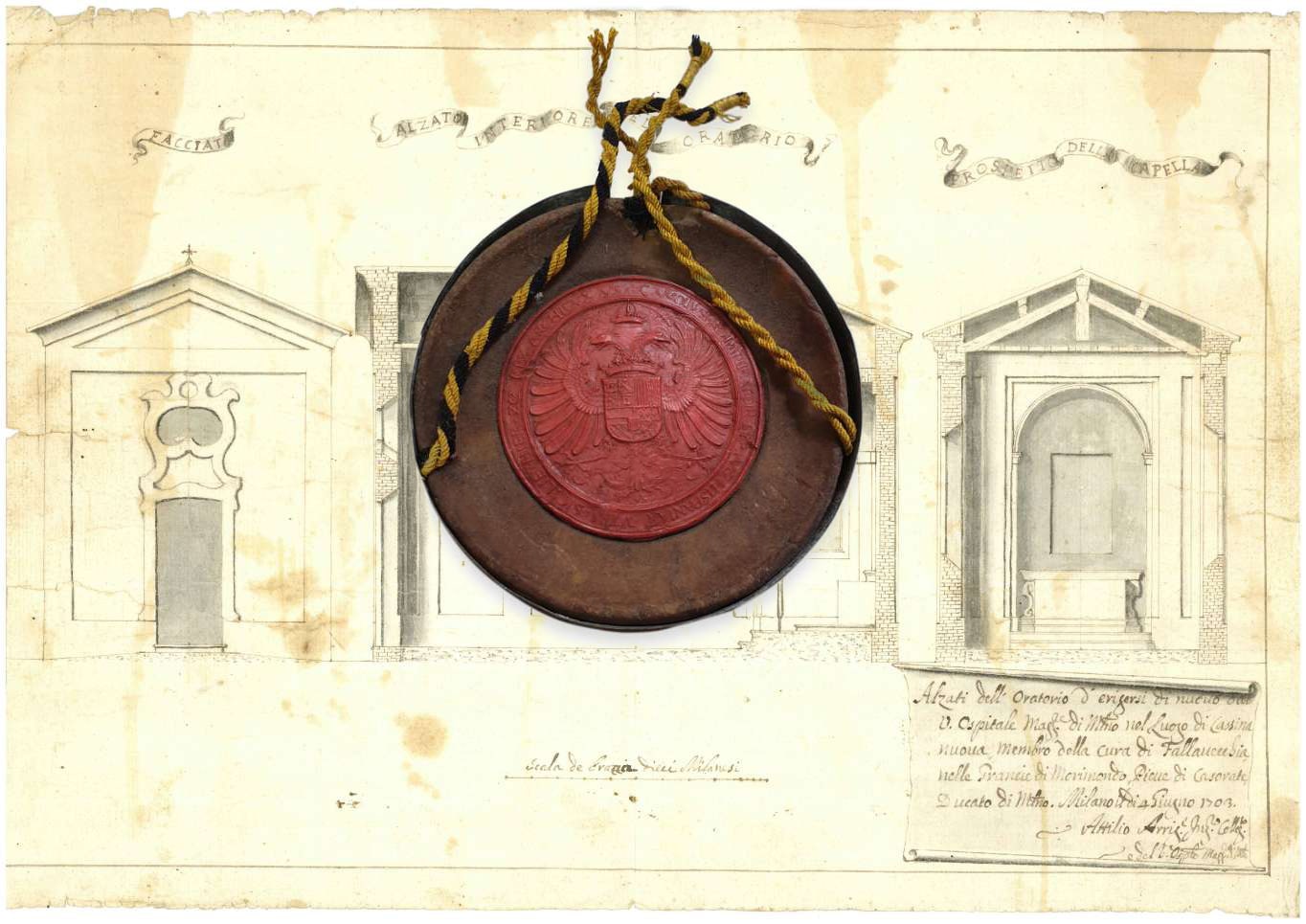

Continuing my journey through the administrative archives, which contain all the documents that regard the hospital from its founding until today, after papal bulls, I also found imperial seals.

In the mid-19th century, when Napoleon, then general, came to conquer the Republic of the Serenissima, he camped at the Abbey of Mirasole in Opera, near Milan. To treat his soldiers, he called the doctors of the Ca' Granda. Once he returned to France, remembering the treatment received, he decided to give an imperial seal to the Hospital, the Abbey of Mirasole, and all the surrounding agricultural land.

So, between papal bulls, imperial seals and bequests from many nobles and important people who contributed to the history of Milan, starting with Bernabò Visconti and right up until today, the Hospital's assets grew to reach 8,500 hectares (around 85 million square metres, of which 1% was buildable, with almost 100 farmsteads) of agricultural land, becoming the largest landowner on the national territory.

When I became President in 2011, the situation was critical: the Hospital had leased the land at low prices, for very long periods (30 years); in exchange, the tenants had to take care of the maintenance that otherwise would have been the responsibility of the owner.

The situation really was difficult: very long rental contracts (fortunately the first 30 years were approaching expiry) with investments never made, asbestos roofs, low rents, a lot of agricultural land made buildable; the only map of our estates was drawn on tracing paper with the properties still marked in Indian ink.

We had no land registry database, nothing digital, and assets that in theory brought income, but that really lost 150,000 euros a year.

But, rediscovering and studying the history of Ca' Granda, I had the idea of returning to our origins, restoring the old role of the Hospital: we created an ad hoc foundation, the IRCCS Ca' Granda Foundation, and in five years, thanks to a dedicated statute, a group of people skilled at managing this type of asset, and great enthusiasm, we managed to map everything and, gradually, as the contracts expired, verify the commitments made regarding their maintenance and redevelopment. We teamed up with our tenants and discussed together what we needed to do now.

We fixed the rent prices, the unfinished maintenance, the due diligence processes, and created a digital land registry database that is accessible to all. The next step was to do the good stuff: we are an ethical organisation, so we need to be ethical with our land, and not impoverish or ruin it.

We worked with our tenants to try and create a more sustainable form of agriculture through an academy that teaches them how, with 13 hectares of land and training grounds where they can learn how to farm using organic methods, focusing on food cultivation.

Not content with this, we also wanted to carry out preventative actions by producing healthier, safer food.

Thanks to the documents found in the archive, we know that the Hospital produced food for its patients and health workers. It is no coincidence that all the farmsteads were only a day away on horseback, to ensure that food did not deteriorate on the journey. So, today we have restored this tradition, but with a modern twist: we produce healthy, safe food that is guaranteed by our own nutritionists and grown locally.

Microfiltered milk and organic rice produced by the Hospital's farmers have returned to the canteen for our inpatients. In the Mangiagalli Clinic, we have set up a shop where it is possible to buy rice, milk, gorgonzola, yoghurt and other dairy products produced in the Hospital's farmsteads. Some of the products have even been sold to large-scale distribution channels.

All the revenue, just like all the money we receive from our leases, returns to the Hospital as research funds. A perfect example of a circular economy!

An interview with Jock Zonfrillo: how he has codified indigenous culinary traditions with a modern twist, recovering products with an ancient history.

Pursuing a great dream: to create a "free-roaming" food culture with zero impact.

Juri Chiotti, the youngest Michelin-starred chef in Italy, tells his story.