A project, a mission: promoting high-quality, sustainable cosmetics to help protect bees, the environment and our own lives.

According to legend, in Ancient Greece there was a dispute between gods over the control of Attica. Poseidon hit the land with his trident with such force that saltwater gushed out. The counter-attack from Athena, his adversary, was very different: she planted an olive tree. Cecrops, the referee of the contest, had no doubts over the winner, and entrusted Attica to Athena. With her gift, the goddess had changed the life of mankind forever. From that moment on, that tree would be a source of nourishment for living beings, a beacon in the night and medicine for the body: those who tried to damage it would be exiled.

In The Constitution of the Athenians, Aristotle declared that anyone who cut down an olive tree deserved the death penalty.

But how can we exile, or condemn to death, a bacterium that attacks and destroys olive trees?

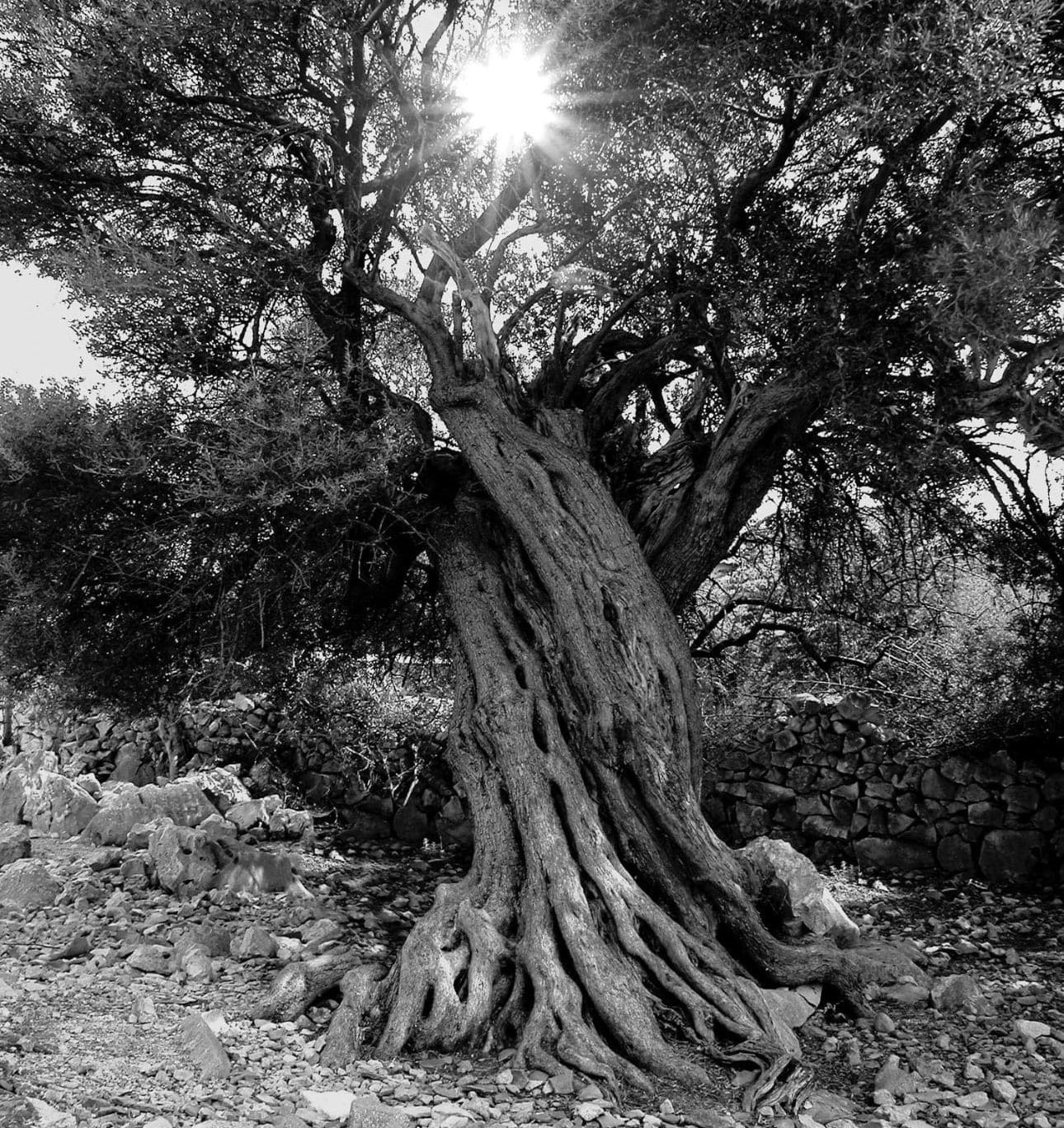

Apulia is the region of Italy with the most significant olive-growing heritage: over 60 million olive trees.

It is also the region with the highest concentration in the world of olive trees that have been alive for centuries, if not millennia. These majestic trees, also known as "patriarchs", characterise the landscape of the Piana degli Ulivi Monumentali, an area of great environmental, historical and scenic value that stretches between the municipalities of Ostuni, Fasano, Monopoli and Carovigno.

This priceless heritage is threatened by the spread of Xylella fastidiosa in the area, one of the most dangerous known plant pathogenic bacteria in the world. It lives and reproduces exclusively in the xylem, the vessels that transport raw sap through the plant, blocking them and causing the olive tree to dry out and die. In order to spread, it depends on an insect able to take Xylella from the infected plant and transmit it to other healthy plants: the Philaenus spumarius, known as the "meadow spittlebug".

Xylella was identified for the first time in Salento in 2013, but it had probably already been present for a few years, and rapidly spread towards the north of Apulia. At the end of 2013, the Plant Protection Service of the Apulia Region estimated the area affected by the spread of the bacterium to be around 8,000 hectares. By the end of 2021, the area marked as being infected had reached over 140km in length, involving 40% of the territory of Apulia, and affecting the entire provinces of Lecce and Brindisi, half of the province of Taranto, and a few municipalities in the Bari area, putting the Piana degli Ulivi Monumentali at risk.

But where did it come from? The bacterium is believed to have arrived with a shipment of infected ornamental coffee plants from Costa Rica. Once in Salento, a series of favourable conditions helped it to spread: the climate, ideal for its survival; a widespread, continuous presence of olive trees, which revealed themselves to be the most susceptible hosts; and the abundant presence of the "meadow spittlebug".

And the damage was done.

Apulia's cultural heritage, which is also economically crucial, has been put at risk by a "fastidious" disease from Central America. As often happens with the appearance of new, unfamiliar events, the initial fight against Xylella fastidiosa had to struggle against manipulation, conspiracy theories that easily captured attention, and unclear and imprecise information, if not actual misinformation.

Precious time was lost, therefore, in carrying out operations to contain the situation, as suggested by the scientific community, which included the Institute for the Sustainable Protection of Plants - IPSP - from the National Research Council - CNR. Consequently, we quickly reached a point at which the bacterium had spread so much that it was no longer possible to expect to eradicate it. Furthermore, treatments that can recover diseased plants are still not available; on the contrary, infected plants must be promptly cut down and isolated. Finally, no cultivars of olive trees have yet been found that are immune to the bacterium; there are only tolerant cultivars: Leccino and FS-17.

We therefore need to continue to live with Xylella, adopting adequate measures to contain it and prevent its spread, and hope for increased knowledge acquired through the continuing research. First and foremost, it is necessary to act against the spread of the insect vector, adopting adequate agricultural measures that can counteract its action, such as: tilling the surface of the soil, regular pruning, and insecticide treatments. Another measure involves planting new olive groves, using the cultivars that are resistant or tolerant to the bacterium.

Finally, in order to protect ancient, monumental olive trees - the "patriarchs" constituting a priceless heritage that cannot be reproduced - currently the only possible approach is to graft Leccino specimens onto healthy plants: trying to maintain the essence of the identity of historical Mediterranean olive groves by inserting a variable of adaptation. A small modification to the identity of our olive trees.

In this sense, Apulia's regional administration has also acted, carrying out a Special plan for the regeneration of Apulian olive cultivation, with a tender for the Protection of ancient and monumental olive trees. Unaprol, in collaboration with Coldiretti Puglia, is promoting initiatives to raise awareness in Apulian olive growers, as well as supporting tangible projects for grafting onto monumental olive trees, and is partnering the Institute for the Sustainable Protection of Plants at the CNR in projects and initiatives to fight against the spread of Xylella.

From an agricultural perspective, the solution of grafting alone - despite being carried out to perfection - is not enough, and needs to be accompanied by a series of measures to increase the intervention's possibility of success: the grafted plants need to be supported with appropriate intensive fertilisation and irrigation to facilitate the attachment and development of the grafts. It is also necessary to monitor, take care of and protect the grafted plants, in order to save their "lineage".

This lineage has an ancient history: the Olea europaea - the scientific name for the olive tree - has its origins in the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. It was first the Phoenician and Greek sailors, and later the Arabs and Romans, who spread olive cultivation along the plains and sunny hills of the Italian peninsula, reaching Apulia, where they found the ideal habitat for growth.

In the National Museum of Taranto, three ancient amphorae are preserved, along with the sarcophagus of an athlete who had participated in the Panathenaic Games (the most important religious festivals), and was awarded with richly ornate vases containing olive oil, obtained from olive trees planted by Solon.

The olive tree has always been considered a symbol of glory, triumph, honour, peace and abundance: tradition narrates that Romulus and Remus were born under an olive tree; in ancient Rome, crowns made from olive branches, dedicated to Minerva and Jupiter, were used to honour valiant citizens and crown the heads of couples on their wedding day; and even the deceased were crowned with them to symbolise their victory in the struggles of life.

The Piana degli Ulivi is the area with the highest concentration of ancient olive trees, many of which have been alive for millennia, and it is in this very area that one of the most ancient roads, the Via Traiana, passes through, built by Emperor Trajan around two thousand years ago to improve communication between Rome, the port of Brindisi, and the East, for the trade of olive oil. This meant that a large number of ancient farms sprang up to the sides of the Via Traiana, each with its own underground olive oil mill - carved from the rock - and olive trees.

These trees have a titanic strength and life force that makes them almost immortal. Almost.

We need to keep our attention focused on the Xylella problem, provide information and communication clearly and correctly, and follow and support scientific research, with the awareness that there will be neither shortcuts nor miraculous cures.

Our generation has a great responsibility: we have the duty to pass down this heritage of olive trees to future generations, just as we ourselves received it thanks to the dedication, commitment and sacrifices of those who came before us. Giving a future to our olive trees means allowing our ancient "patriarchs" to continue to be present for future generations.

A project, a mission: promoting high-quality, sustainable cosmetics to help protect bees, the environment and our own lives.

From meetings among friends to exchange unused items, to the foundation of a charity that teaches a culture of responsibility and environmental protection.