The Green Drop Award recognises the films that best interpret the values of ecology. From chronicle, to exposé, to prophecy: all the force of environmental cinema.

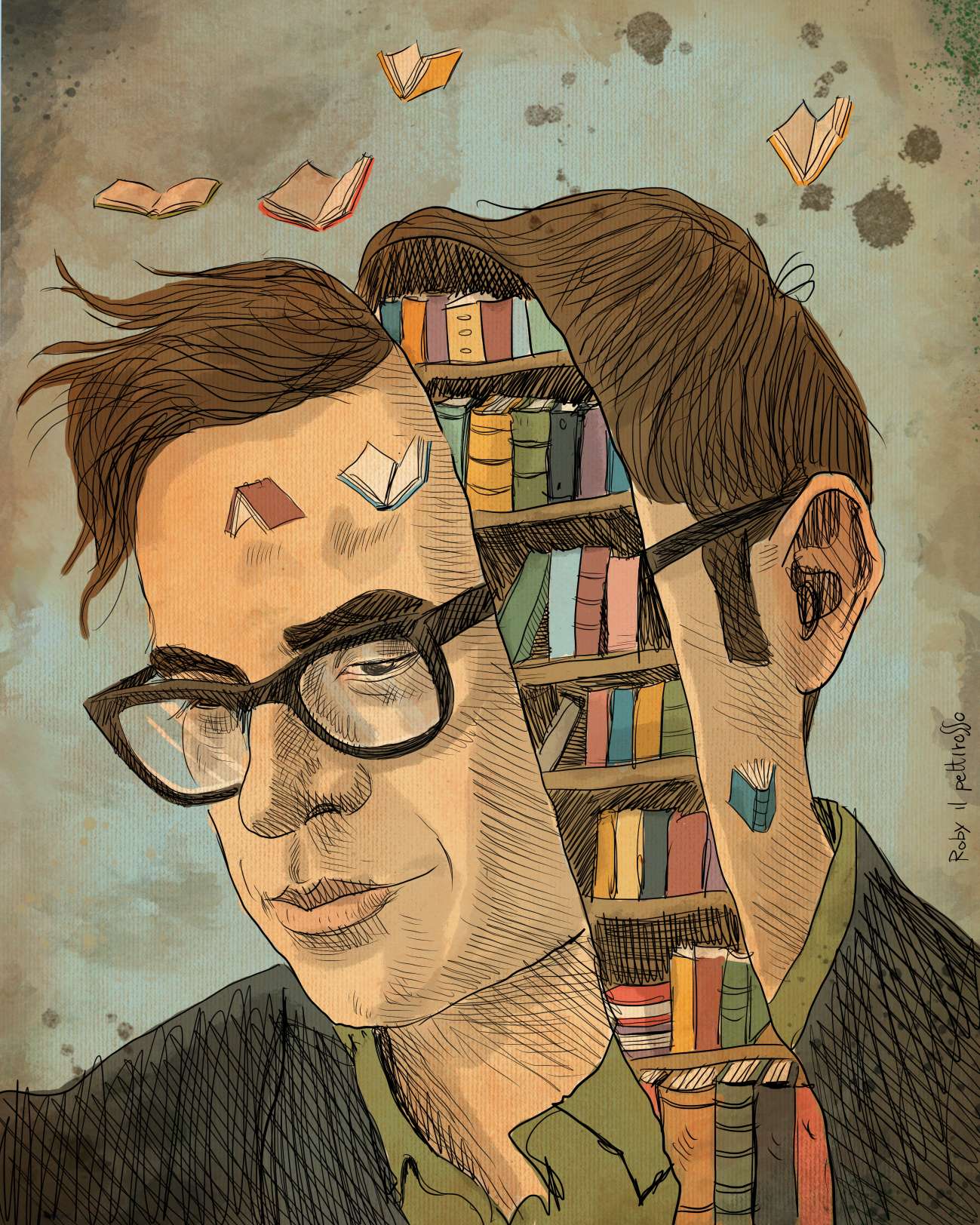

Reading and building identity

Books do not solve practical problems. They don't overcome economic crises, they don't prevent wars, they don't cause the worst governments to fall, they don't avoid personal disasters such as divorces or conflicts with relatives. They don't bring lost loves back to the present day. And yet, they can save our lives. Or, rather, that particular form of life (an amplified, richer, deeper life) that belongs to those who let the demon of reading in. It happened to me.

Umberto Eco maintained that those who don't read, when they reach 70 years old, will have lived only the amount of time of their chronological age. Instead, those who read will have a much longer history under their belt: there was the time Cain killed Abel, the time Ulysses deceived Polyphemus, the time Catherine kissed Heathcliff, and the time when the infinite was made possible by the obstruction of a hedge, in Recanati. It was also Eco who maintained that the book, like the spoon, was a definitive invention. It is difficult to improve on it. Almost impossible to find a tool that is able to convey human thought (that unique mix of intelligence, emotion and imaginative capacity) with the same fidelity as literary language printed on thin paper pages.

But at five years old, I did not know all this. I lived in a house where books were not present. My parents were the children of farmers, who were themselves the children of sharecroppers. Thanks to the economic boom, they managed to pull themselves out of a long tradition of poverty and illiteracy that their ancestors had been faithful to, so to speak, for a long time. My father read the daily newspaper after lunch. My mother had read novels in her youth, but now she didn't have time. If I wanted to find books, I had to go to my maternal grandparents'. This was strange. My parents had a higher level of education than their own parents. Nevertheless, my grandparents, for whom reading a novel was more difficult than pruning a vine, maintained that a house with some books in it was a sign of culture. Books were the guarantee of a lively household in a free, modern country.

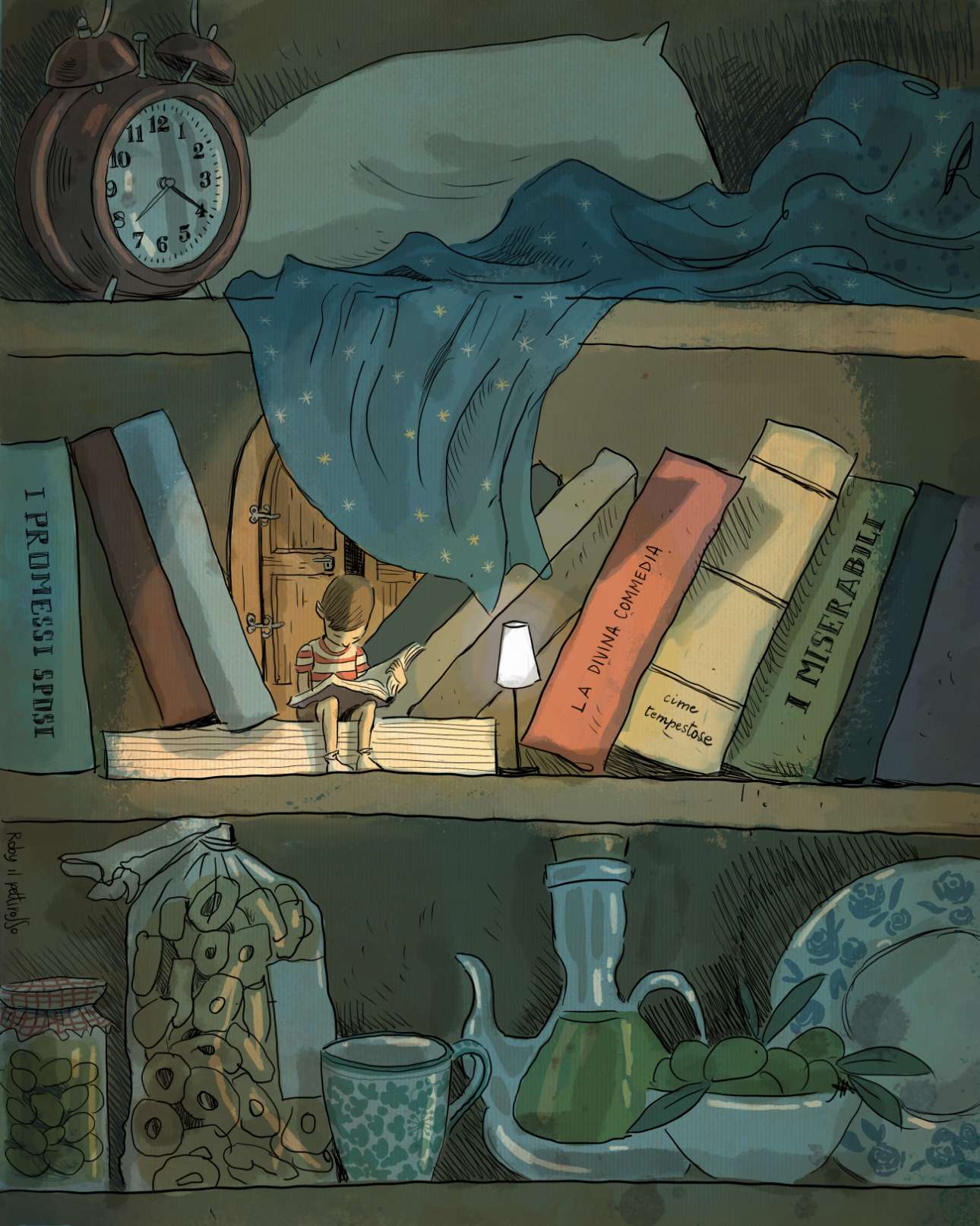

In some farmhouses, there was a mezzanine. An intermediate level between the ground floor (where there was the dining room, the kitchen, and, on the outside, a little vegetable garden) and the first floor (where the bedrooms were). My grandparents' mezzanine contained a dark room, half storage closet, half dwarves' cottage, with a very low ceiling, and a bed where an adult would only have been able to fit curled up. Velvet at the window. An old nightstand and glass ornaments.

The books were kept in this room.

Today, my library contains a few thousand volumes. I run my hand along their bindings, tracing my own sentimental grammar. But these many books would never have existed without those initial few. There were six books in the mezzanine at my grandparents' house: The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni, Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë, Les Misérables by Victor Hugo, Peter Pan by James Matthew Barrie, and The Happy Prince and Other Tales by Oscar Wilde.

When we went to visit my grandparents, I would drag my mother to the mezzanine, begging her to read me one of these books. We would perch uncomfortably on the dwarves' bed, and turn on the table lamp that lit up only the area around her hands. My mother would pick up the book and begin to read. And I would be catapulted into another world.

Whether it was the otherworldly travels of Dante or the romantic madness of Heathcliff and Catherine, I was not just listening to an exciting story. I clearly felt (and I felt it as if through an unfamiliar sense, as if a new organ had sprouted inside my body) that my mind was faithfully following the journey the minds of these great writers had made. The voice of my mother, absorbed in reading, deposited all this inside me, allowing it to materialise in a mysterious zone that involved my heart and my brain, my stomach and my spine, which the ancients called the "soul".

As Joseph Brodsky maintained, if what distinguishes us from other animals is our use of language, and if literature is the highest linguistic form, then it is also the destination of our species, our anthropological purpose.

After my enchanting period in the mezzanine, I became an avid reader. Novels. Poems. A lot of comics. I devoured a book a day. I immersed myself in their plots, neglecting everything else, my schoolwork included. I felt that extra organ I spoke about grow inside me. I believe it is the secular equivalent of what certain religious traditions call the third eye.

Through reading, it seemed that I was able to see the world in a more complex way, more intensely, more profoundly; it seemed that I could feel others, and consequently myself, too, with a force that I would not otherwise have had. Above all, it seemed that I could become other people, a discipline that is practised less and less in this era of narcissism and constant self-expression.

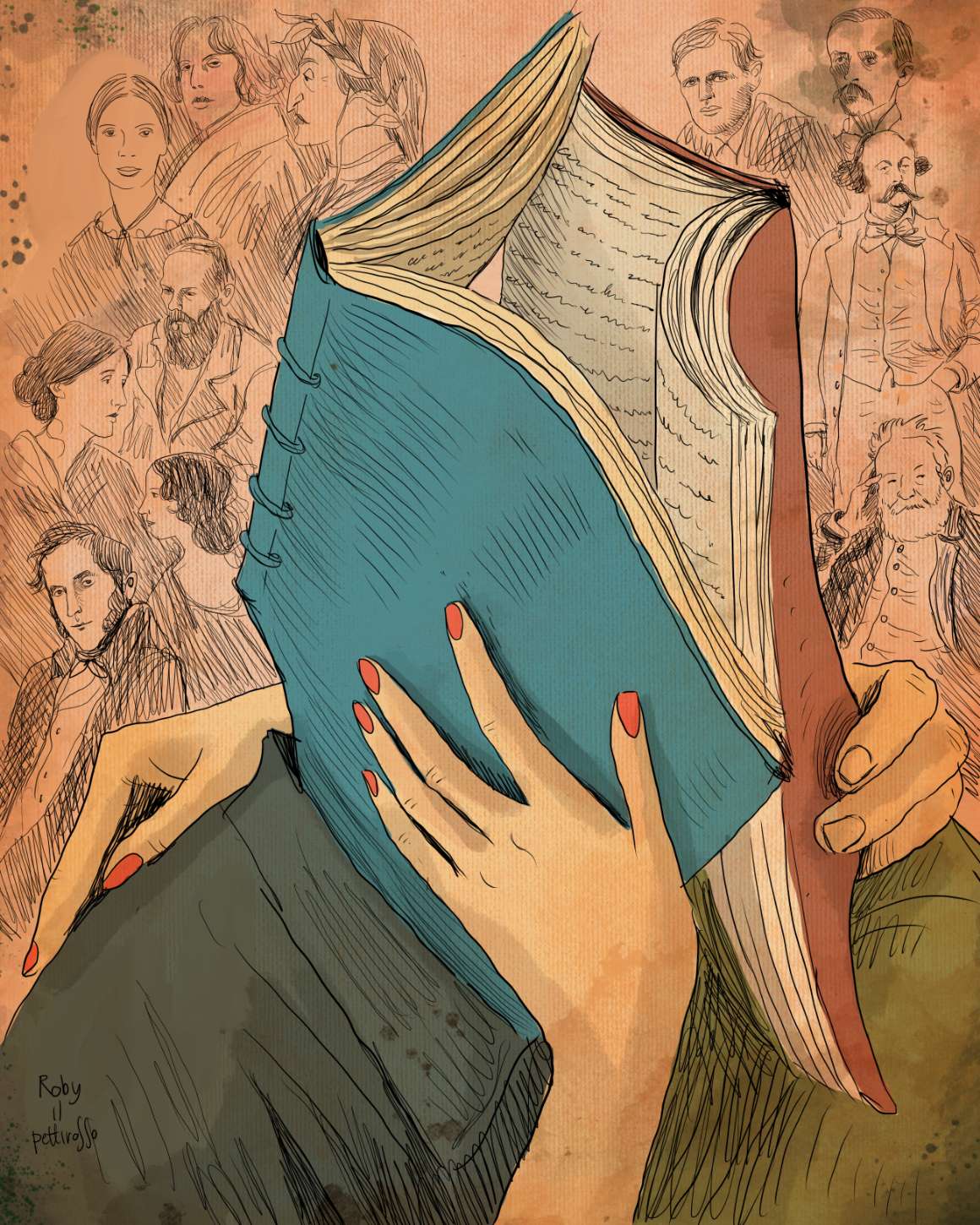

We read Gustave Flaubert and we become Emma Bovary; through Virginia Woolf we are Clarissa Dalloway; with Dostoyevsky we put ourselves in the shoes of the brothers Karamazov; and when we read Jack London, we even transform into a dog, a tree, a starry sky!

All too often we live trapped in the cramped prison of an ailing ego. Reading can release us from that cage. It is not by looking in the mirror that we will understand who we are. We get to know ourselves, and build our identities, only through others, thanks to a constant game of differentiation and identification, of distance and proximity, which it is our task to activate.

Knowing how to recognise others (until we see things through their eyes) is therefore fundamental. But reading can take us by the hand to lead us towards an even bolder undertaking: making us feel less alone by reconnecting us with the world, to what we call nature, and maybe should call the cosmos. Becoming, thanks to books, another man, a young girl, a child, an old person, a soldier, a priest, an Amazon, a tyrant, a hero, an ordinary person to whom extraordinary things happen, and even becoming a cat, a whale, a horse, a unicorn, a dragon, a blade of grass, a tree, a gust of wind... until, book after book, transformation after transformation, we finally start to feel that we are part of a whole - us, other animals, trees, flowers, every slice of creation: all connected in a universal spirit.

Breaking the sad barrier that makes us lonely and self-referential is one of the most important tasks that the 21st century has assigned us. We are not at the centre of a scene that is separate from us; we are part of it. On closer inspection, there isn't even a real centre: we are floating around, constantly changing places; we are everywhere, at the same time, in a cosmic dance that explodes with every blink of an eye. Books - these old friends, masters of internal liberation - can remind us of this.